An Introduction to Inevitable Failure

A New Media Artist's Guide to the Risks and Rewards of Ephemeral Platforms

© Andy Deck, 2021

What are the rewards of ephemeral platforms? In an era of consumer electronics, ephemerality is often seen as a nuisance or a hindrance to personal productivity, but it has other resonances in the sphere of culture. In the words of the artist and writer David Antin, “you could make the most disturbing public art in the world and nobody would give a damn, [if they knew] that after some limited time it would go away.” (Fine Furs, p.162) Responding to the controversy surrounding the removal of Richard Serra’s tilted arc from a plaza in lower Manhattan, Antin writes “I don’t think public art installations should be permanent. I think they should be wreckable. I think we should have a ceremony of destruction and remove them regularly. I think works like Serra’s work should after some specifically limited time have been publically destroyed in an honorable fashion. This ritual would not have meant that the work was bad, but that it had said what it had to say.”

Though Antin was writing two generations later and in a far less bombastic frame of mind, there are strong parallels between his arguments in "Fine Furs" and those of F. T. Marinetti, the textual leader of Futurism. The Futurists dreamed of destruction and ephemerality. As Italian creatives they were in the shadow of classical and Renaissance achievements that had been preserved for centuries, like immovable objects blocking their paths to glory.

The remedies proposed by the Futurists for annoyingly permanent fixtures of culture were mostly impractical. Those offered by Antin (“My solution was soluble architecture”) sometimes strayed into the surreal. In the present, however, with respect to electronics and electronic media, impermanence is basically an unavoidable attribute. In order to attain a semblance of permanence the largest tech companies must marshall the genius and energy of thousands of diligent innovators. Yet the CEOs of these companies must sleep with one eye open wondering what false step to avoid. Even the seemingly oracular Bill Gates failed utterly to comprehend the importance of the Internet and the World Wide Web in his book The Road Ahead.

In 1994 when the World Wide Web arrived, there were many large institutions and corporations that were caught flat footed by the emergence of online media. The period of multi-media distributed on CD-ROM gave way suddenly to immaterial digital media. In the 1990s millions of websites sprang up, the fruits of a network that had not been design for cultural or popular use. For a time, websites by individuals and small organizations rivaled the offerings of more established institutions because there was a new way that people were communicating and gathering information. In short, new technological possibilities had caught large media companies by surprise and the result was an upswell of creativity, competition, and innovation.

Computing became entwined with more and more genres of art, from Video Art to Installation Art. It wasn't long before iPhones and tablets became a powerful new creative outlet for tech-savvy makers. App culture exploded into people's pockets and began to rival the diverse offerings of the Web. Throughout this period creative individuals had countless opportunities to chart paths in art and entertainment, responding to the new productive possibilities, from affordable computing and consumer electronics, to inexpensive networks of distribution.

When big mainframes were used for dry number crunching the computer was a symbol of oppression for many. Since personal computers began to proliferate in the 1980s, those biases against computers have faded. Increasingly computers are even tolerated in museums, though they may be hidden from view. As adults in most places are busy working with screens, children grow up predisposed to want to interact with screen media, too. Art education now embraces digital processes, too. Before most young people set foot in a museum nowadays, they are already aware of a whole host of intriguing digital cultural products and production techniques. Aspiring creatives today gravitate toward the opportunities and capacities of new technologies. They are drawn also to the new ideas and experiences that can be evoked through electronics, immersion, and interaction. Notions of progress and the promise of riches probably contribute to this embrace of the new. In short, the adoption of highly technological tools is now in an advanced phase, affecting the day to day creative activities of millions of people.

But this picture of bounty and opportunity isn't the whole story. Vulnerability to impermanence is another dimension of the current conditions for creativity. For example, in the sphere of Web publishing, generating content was fairly straightforward in the Web's infancy. Today content is consumed by a whole gamut of personal computers, smartphones, netbooks, tablets, phablets, laptops, e-readers, smartwatches, televisions, game consoles, digital signage, and elevator displays. Keeping up with this kind of diversification is only half the battle. Since social media platforms have established a beachhead in the war for attention, publishing has become almost synonymous with marketing. While large corporations can dedicate teams to address these types of challenges, individual artists and arts organizations don't usually have such options.

The pace of cultural appropriation of new technology has mirrored the productivity of the tech sector. In the decade following the dawn of the Web, fads in technology-related art came and went, from Net Art, to Second Life, Game Modification, and Machinema. No sooner had they emerged than they were being eulogized and historicized. Arts organizations like Turbulence commissioned and archived countless innovative projects from 1996 to 2015. Perhaps Turbulence did ride a wave, but it was more like surfing a half-pipe. Under the weight of fundraising, archive preservation, and marketing, it was bound to collapse.

Digital media and the Internet provide an opportunity for artists and arts organizations to extend the impact of the arts. Live performances can be enhanced by opportunities for further engagement and education. Many more people can be reached with an article or video than with a one-time lecture.When the new arts and new media are formulated as old media "enhanced by opportunities for further engagement," what's not to like? Insofar as the enhancements arise from straightforward distribution of images and sounds, problems like preservation are less scary and the benefits are clearer. For digital and electronic creative practices, however, forays into experimental and unconventional approaches tend to lead to thorny problems.

— PEW Research summary

"Arts Organizations and Digital Technologies"

In some periods the most popular media have also been relatively easy to preserve, even for centuries in some cases. The present day is not such a period, for although stable media (marble sculpting anyone?) continue to exist, the weight of creative production has now shifted toward more dynamic and transient artforms. Artists now produce a lot of immaterial objects and media — especially interactive media — that resist preservation, though not always on purpose. In many cases the ephemerality stems from shifting technological norms and practices, and manufacturer business models that discourage reuse, preservation, and restoration.

Interactive and electronic media are deeply impacted by this instability. Despite the billions of hours of labor that went into building the first decade of the Web, most highlights of online culture in that period are now fading from living memory, supplanted by the emergence of cellphones, tablets, and app culture. Electronic media art follows this tumbling technical trajectory. The creative achievements of the latest wave will follow a similar path to oblivion. It's not only the mundane products that degrade and disappear: the most impressive and aesthetically sophisticated works tend to be plowed under, too, though they may be documented variously and kept on "life support" longer. Consider for example the florescence of CD-ROM culture that occurred in the years preceding the arrival of the World Wide Web. Briefly it seemed as though the format could establish a market. Along came the Web! So much for the seeming permanence of the optical disk. Now, opportunities to experience those diverse multimedia products have become rare.

The point is not that cultural experiences can disappear. They do. The decline of the great Library of Alexandria is symbolic of how our continuity with the past has been broken in countless ways. Clearly reverence for the past comes and goes. Modernists in the 20th century, driven to innovate and to seek differentiation, began to actively neglect the durability of artforms. From the Cabaret Voltaire to the Self Destructing Machine of Jean Tinguely, experiences themselves took precedence over their preservation. Pleasing the collector took a back seat. The newsprint photomontages of the Dadaists, for example, were not exactly formulated to achieve long-lasting products. Although most museums continue to valorize and prefer unique and preservable objects, art over the past century has challenged this mission in many ways. While dematerialized and conceptual practices offer clear examples of this resistance, the embrace of mechanical reproduction in photography and film has also undermined the unique and preservable object in a profound way. Fast forward to the present and we find a visual culture that in many ways develops in reaction to the superabundance of recordings that linger. The capacity for disappearance has become a feature, as evidenced by the popularity of Snapchat and other disappearing stories.

It's as if the painting, absolutely still, soundless, becomes a corridor, connecting the moment it represents with the moment at which you are looking at it, and something travels down that corridor at a speed greater than light, throwing into question our way of measuring time itself.

— John Berger, Ways of Seeing

Something unprecedented is taking place in the arts, as more and more unstable technological ingredients get baked into artistic products and processes. While there is unquestionably a superabundance of digital photography and video, other cultural forms that are more reliant on specific hardware and codes are part of decline in aesthetic "longevity." Works that can't be experienced in a century won't operate as Berger described, collapsing time and allowing an encounter with the artist's "moment." Is this capacity of art threatened by the present devotion to obsolescent artifacts? At what cost to social memory? Museums and their curators and conservators are studying the problem (e.g. the Tate's Reshaping the Collectible project). Twenty years ago the Guggenheim devoted attention and resources to the Variable Media initiative through lectures and exhibitions. But it's a bit like the way that climate scientists are developing ever clearer models of the impending damage that greenhouse gases will cause in the years to come. The root problems persist.

Computer hardware "dies." There are so many ways that electronics fail, relying as they do on bits, components, circuitry, and fluctuating protocols. A digital artwork can malfunction suddenly. Or slowly. Quietly. Explosively. Accidently. Ritually. By design. In response to market forces. Obviously. Mysteriously. Thirty years of experience making digital art has given me a front row seat in this unfolding drama. In my work that involves Net Art, a lot of the maintenance involves source code, server software, changes in protocols, and changing media infrastructure. I have elected to maintain as much control over the adaptation of the individual works as possible.

I have spent decades reviving and maintaining older work. It's a choice that has extracted a price, since one cannot make as much new work while preoccupied with repairing and maintaining an archive of tempermental older works. Some artists have managed to offload responsibility for conservation and maintenance to collectors and institutions. This transference raises questions regarding the authenticity of versions that are modified to resolve the inevitable failures of electronic media. Selling a digital artwork that operates as a piece of software can open the door for owners to change works. This isn't exactly unique, since art restoration can change and botch paintings, too.

But whereas it is possible to preserve a painting for decades and even centuries by protecting it from the elements, a work comprised of electronic components, codes, and circuitry seldom lasts more than a decade or two before it requires restoration of some kind. As just one example, works by video artists like Nam Jun Paik sometimes rely on cathode ray tubes that are no longer manufactured. Faced with logistical problems like finding replacement parts for Cold War era televisions, curators face difficult decisions about ways to exhibit aging classics like Paik's Magnet TV (1965). The essence of that work lies in the effect of magnetism on the appearance of the cathode ray tube. Swapping out the 'tube' for a newer display technology like a flat screen would utterly destroy the work. Curator Chrissie Iles, who encountered such issues in putting together the 2019 exhibition Programmed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, has argued that the curator and institution must dedicate themselves to the "preservation of the experiential integrity of the work." While this is a laudable ideal that is often achievable, the devil is in the details.

Paik produced a considerable body of work involving televisions that he knew would not last forever. A substantial amount of his later work involved additional sculptural elements, like large cages that contained televisions. This was apparently an effort to produce objects that would feel exhibition-worthy even after the televisions stopped working. Duchamp's work Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics), though equipped with an electric motor that could certainly be replaced or repaired, is exhibited primarily as an inert object because the Museum of Modern Art directors have judged that the work is too precious to allow it to move as was intended. Clearly the "experiential integrity" principle is not an ideal that all owners and institutions embrace.

To be fair, the maintenance of a substantial number of technically complex works is a bit like bailing out a barge with a bucket. Obsolescence is a relentless adversary. Smaller institutions and galleries without specialized conservators are not well equipped to deal with these problems. In 1997 a New York City gallery mounted an exhibition named "Mac Classics" featuring art that used early Macintosh computers as its platform. Not all the artists wrote software for the show, but several did. It was already a bit of a gamble to put together such a show in 1997, without a significant budget for reviving and sustaining teen-age hardware, some of which over-heated. Attempting to recreate the show today would be a great deal harder and more expensive, as nearly all the hardware and software that was used is now scarce. Without a doubt a majority of the devices and codes are now lost, damaged, or dysfunctional. Although I have tried to maintain the diskette data and Macintosh hardware from my work in that show, it would now take me a year to restore the artwork that I made in a month — and it would require luck, an engineer, and a generous grant.

The devices and electronic components that artists use are not, generally, designed to last for very long. In fact, the electronics that artists employ are often designed to fail quickly in order to motivate consumers to upgrade to newer models. "Right to repair" advocates have been attempting to bring pressure on manufacturers to design their products with repair as a possibility. In 2018 the movement pursuaded the U.S. Library of Congress and its Copyright Office to allow people to circumvent impediments to repair that had previously favored the rights and prerogatives of corporations. Notwithstanding a few victories in the pursuit of greater freedom to fix things, the overall trend isn't encouraging. Despite the existence of a few open hardware platforms, like the Arduino, that are transparent, the norm is patent entanglements, secrecy and obstruction. Proprietary hardware dominates the terrain of cellphones, tablets, cameras, and notebook computers, all of which are designed to be nearly unrepairable. Miniaturization contributes to the problem: as electronics shrink, it becomes harder and harder to swap out parts.

What's more, it's not only the elements requiring delicate industrialized fabrication that complicate the preservation of electronic artistry. Many works depend on coded instructions, and software systems are forever changing. My own battles with obsolescence fall mostly into this category. As a 'net artist' I have experimented in the context of Web browsers and servers for almost thirty years. Since this period corresponds to the first three decades of the World Wide Web, the technical evolution has been prodigious. Although thousands of artists and creative programmers have developed intriguing work in this new medium, most of that work has died on the vine. Specialists might be able to demonstrate some of it by emulating archaic operating systems, but the servers that delivered the goods are mostly offline. The content has been abandoned, corrupted, or rendered obsolete by changes in software and hardware. Widely used early Web technologies that have been important to my work, like the Java applet and the Flash plugin, have gone the way of the telegraph and the laserdisk.

In some cases the "experiential integrity" can be preserved. Some Net Art classics have been restored in various ways. The Sodaplay Constructor has been restored to a degree, though not by its creator, Ed Burton. One admirer of the original work, an avionics software engineer named Peter Fidelman, took on the task. He decided to prioritize making the code brief and easy to read. Separately, another volunteer restorer, a professor of computational physics named Maciej Matyka, estimated that he had restored 50% and shared that he planned to continue neglecting the piece's audio synthesis, adding "is it needed anyway?" The Sodaplay Constructor lives on after a fashion, but filtered through the interests of its fans.

For works of Net Art that incorporated software development and nuances of interactivity, the fairly radical interventions that are required to revive them seldom lead to a completely equivalent result. Having personally restored a substantial number of my own interactive works over the past decades, I cannot think of any that are exactly the same after the restoration.

Without the artist's voice in the process of restoration, it can be even more difficult to establish what changes are appropriate. In a discussion of a restoration of a pioneering interactive video artwork by Grahame Weinbren and Roberta Friedman, the programmer Isaac Dimitrovsky asked in 2004,

where do we draw the line at modification of the original system’s behavior? ... I think the answer is fairly clear – if the original system has errors that would sometimes cause it to crash or otherwise clearly cause errors, this would probably not be considered an essential part of the original system experience that must be emulated! In other cases (ex. response time or image quality), the value of "improvements" to the original may be debatable. For example, the initial working version of the updated Erl-King had a substantially faster response time than the original to switches in the played video. The artist decided that this in fact degraded the viewer’s experience, so we slowed down the video player switch to match the original speed. — Isaac Dimitrovsky, Final Report: Erl-King project

Eliminating processing delays is such a common preoccupation for software engineers that it's easy to forget that it's not an unmitigated good. Apparent technical progress can interfere with people's comprehension of what they are seeing and doing. The whole idea of "original speed" is complicated by the fact that human perception is a variable. As technology advances, changes in people's expectations of appropriate timing can make original speeds feel wrong. In any case, without a functioning original version of the work running on legacy hardware and software, it's often difficult to know just what the "original speed" was!

So much has changed with regard to user experience design over the past few decades. Changes in behavioral patterns and expectations present the artist with hard choices about whether to alter works in restoration to make them more appealing or comprehensible, in light of contemporary habits of viewing and interaction.

Dimitrovsky remarks that image quality is another area where "improvements" "may be debatable." Software engineers seem to hate pixelization. For years artists and game designers have embraced the pixel as a graphical element — beautiful for all its jaggedness. Nevertheless, software engineers who have influenced the evolution of most graphics utilities apparently believe that all lines should be smoothed using a technique called "anti-aliasing." The devotion of operating system and browser developers to this pixel blending is so thoroughgoing that backwards compatibility with older pixelated norms has been neglected for decades. A work that initially relied on aesthetics that were woven into popular graphical frameworks (e.g. the Java applet) can be very difficult to recreate within a new graphics implementation. Restoration of even basic operations like drawing a line can present aggravating challenges.

Because hardware, operating systems, and software libraries change over time, even the most well-meaning restorer of digital art can easily miss inconsistencies that accumulate over time. Some technologies that continue to exist over decades have nevertheless evolved in significant ways that present profound preservation challenges. In the late 1990s I began to employ the new PHP "server side" language. As PHP became more widely adopted, the developers made frequent modifications to its programming norms and procedures. Due to these frequent updates, code written in PHP has required many revisions. This illustrates how online interactive software must evolve to remain functional. Since the mid-1990s I have built and maintained a succession of six different servers to host my online work. Because it is not practical to maintain old operating systems when setting up new computers, application software must be compatible with new operating systems. For me this has meant that each new server installation had a higher version of the PHP language. Thousands of lines of code needed to be brought into conformity with new versions of PHP. The rationales of the PHP developers often have felt maddeningly arbitrary, but in truth it's mostly that the developers were focused on "enterprise" logistics rather than the preferences of an artist.

In the early period of the Web, the most common factor motivating language and software changes was security. In the late 1990s socket communication between servers and web browsers was fairly unrestricted, a hold-over from a less complicated era of Internet development. This openness enabled me to synchronize distributed multi-user interactive art. At the turn of the century, however, highly restrictive firewalls became the norm and most people did not feel confident enough to open "holes" in their firewalls to experience Internet art. For years, I tried to get past this problem, which effectively blocked my most popular works. A decade passed before I figured out a way to defeat the problem. Ironically, most of the nefarious things that led to stricter firewalls in the first place are still possible. After years of rearranging the deck chairs, countless Internet security updates have accomplished at least one thing: anyone experimenting with the Internet as a creative medium must be prepared to contend with an array of annoying security protocols. In the competition between Internet security and Internet art, art lost something important: unlike before, expertise in network security is now prerequisite knowledge.

To be fair, there were consequential drawbacks to the browser designs of the mid-1990s. Some features and functionality in early Web software and media were used both for artistic purposes and for unredeeming exploits. Even so, the reaction of browser developers was not nuanced. All major browser developers removed numerous features ("vulnerabilities") that were deemed problematic. These restrictions tended to make creative use of the medium more complicated and less fun, especially for independent artist-developers. From pop-up window blockers to encryption, the landscape evolved quickly. Rambunctious works of Net Art designed to leverage browser capabilities circa 1997 were rendered docile by upgraded browsers. Overnight a whole Net Art sub-genre of browser window control was blocked, including outstanding work from JODI, Jim Punk, and others. This illustrates an important attribute of electronic media art that might be called the "indifferent host." Whereas media such as oil on canvas have an established importance in the gallery art context, the markets for electronic devices and software treat artistic usages as minor curiosities. Instead of stirring the drink, artists ride the wave.

Actually it was this idea of "riding the wave" that attracted me to the personal computer in the late-1980s. For many people, being an early adopter of the computer as an artistic tool, and medium, has opened doors over the past few decades. Computing and digital technology are intertwined with such a vast array of artistic products today that any attempt to voice caution about the limits of these strategies must be balanced by an acknowledgment of all the interesting and innovative things that have become possible and real due to engagement with new media and techniques. Preservation and archival conservation are not the only measures of aesthetic quality, after all. Many artists don't even try to fight this losing battle of restoration. It's a bit obsessive after all. For transient experiences, histories can be written that represent them with words and pictures, freeing artists to move on to new things.

Out with the old! In with the new! It’s certainly an attractive approach for the spirit of innovation. Is it the right way to think about working with technology? Is it best to document ephemeral electronic art and then let go of it rather than fighting against the tide? An artist could hardly be blamed for adopting this approach.

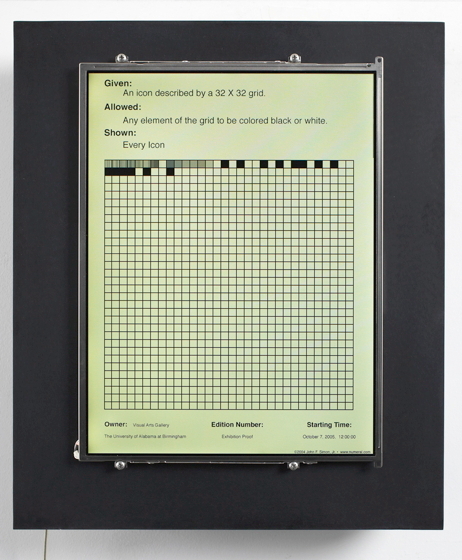

"Mostly I feel like when they quit out that should be the end but the market doesn't agree." — John F. Simon, Jr.Still, as John F. Simon, Jr. expresses aptly, the collectors and institutions may not "agree" with this carefree path. There's not only a weight of tradition driving preservation, there's also the simple economics of return on investment.

A similar pressure has developed in the sphere of app culture, where content producers are being pushed to deliver and maintain content within shifting device and software infrastructures. Software portals like Apple's App Store have the power to drop titles if they don't stay on the iterative update merry-go-round, meaning that keeping a creative work in that venue requires persistent adaptation, compliance, and maintenance of codes. Updates and support demand a persistent service relationship that may not be desired by the developer. But unlike websites, which may degrade gradually through neglect, apps disappear from the "store" abruptly when developers stop jumping through upgrade hoops, or cease to pay Apple's annual "developer license" fee.

Of course, revenue from these app portals can also benefit artists and developers. Despite the strong-arm tactics, it is arguable that the value of app stores lies in their predictable regulation of popular and functional products. It's like a mall of fungible attractions. While specific products may come and go, services and experiences that people want are maintained.

Is the culture of interactivity trending inexorably toward this 'adapt or get swapped out' model? What else could continuity look like under conditions of changing infrastructure? With respect to Web design, organizations have realized that bulldozing websites and replacing them every few years is costly and unpopular. Even before the launch party ends, complaints mount from users who spent years learning the previous interface and functionality.

"...massive organizations are taking cues from the smaller, leaner startup world and striving to get things out the door quicker. By creating minimum viable products and shipping often to iteratively improve the experience, organizations are able to better address user feedback and keep up with the ever-shifting web landscape." — Brad Frost, Atomic DesignDo iterative modifications to a "minimum viable product" strategies work in the arts? Although business customers are amenable to a series of service upgrades, the work of art has traditionally been idealized as consistent from one era to another. Artwork that iterates and evolves is at best like a tolerated house guest within the established curatorial and art historical enterprise. Art designed to changed serially is clearly the exception rather than the norm. Then again, what passes as art today would be a surprise to 19th century visitors, so new modes do emerge.

Some artists have responded to the problem of preservation by working within corporatized media management systems that maintain and leverage contributed content. While it may be comforting that Google's army of engineers is working to preserve petabytes of video, in server farms shielded by reinforced concrete, it won't be a great trade-off for aesthetics if the roles of intellectuals are supplanted by restrictive software algorithms. YouTube's removal of artist Petra Cortright's "VVEBCAM" is emblematic of a tone deaf rapport between corporations and intellectual freedom, creativity, and the exploration of boundaries. Cortright's video contained nothing offensive or controversial. Only its textual "meta tags" were deemed unacceptable to YouTube's algorithmic censorship mechanisms. While Cortright's video has been preserved elsewhere, YouTube's control regime represents a very different posture toward innovation than the World Wide Web represented in its infancy. Despite the variety of content within its videos, YouTube, and many other platforms that aspire to be like it, specializes in delivering uniform content. As regimes of soft censorship like YouTube's become increasingly the norm, the conditions for experimentation and social memory erode.

In an era of rapid technological change, with conditions that are simultaneously disruptive and productive, this tumultuousness has undoubtedly provided opportunities for many ambitious, experimental innovators. Yet with decades of hindsight it's clear to those with eyes to see that for all the bottom-up success stories, there has been a pronounced growth of very large corporations that profoundly influence culture. Tech giants have accelerated the disappearance of Web 1.0 content, supplanting it with their own offerings. Clearly a preparedness to exploit instability can empower corporations as much as individuals. With the continued deployment of artificial intelligence, expert systems will be used increasingly to induce predictable human behavior. If online news institutions can be reduced to emulating successful click bait strategies, the arts may be next. Visitor totals and various other metrics do matter in contemporary museum management. If arts institutions follow this machine learning path of optimizing return visitors and store purchases, the traditional archival project may become subordinate to marketing. Perhaps museums are bound to make more concessions, opting for alternatives to preservation. When it becomes too costly or complicated to resurrect temperamental and idiosyncratic works, there's always something newer that scratches a similar itch. Does "user experience" weigh more heavily than the historical mission?

Whether the agents of historical preservation are collectors, arts organizations, museums, artists, app stores, or corporate media management systems, it's hard to avoid the conclusion that the foundations of this project are failing. There are so many logistical problems in the preservation of digital culture today. Despite a persistent bouyancy about the potential for technical solutions, we are surrounded by the detritus of electronics. The knowledge and equipment required to resurrect artifacts are not easily recaptured. Mixed metaphors like entropy, endangerment, and extinction feel apt, and there is no cavalry riding to the rescue. To the extent that creatives continue to embrace the fascinating potential of new electronic and software-enabled artforms, these trends of disorder, decay, and dissolution will continue to impact histories of technological culture. Although emulation and adaptation of some platforms and media types will undoubtedly lead to the archiving of massive amounts of data, the conditions for restoring the experiential integrity of experimental and unconventional works will remain poor. There is no silver bullet solution to these intractable problems. This introduction can only focus attention on the dilemmas. Perhaps critical engagement with the ways that the arts are changing, and an emerging historical sense of the art of the information age, can help to inform the next waves of electronic artistry.

References

© Andy Deck, 2021